A third generation blockchain

SEGMENT Technologies

If the mathematical, algorithmic, cryptographic, or methodological questions are complex to address, the solutions provided are just as complex.

This page discusses the core technologies used by SEGMENT without going into codes and technical details that are difficult for non-professionals to access. It offers a global overview – certainly insufficient for experts on these matters – of the approaches developed within SEGMENT.

Cryptography in SEGMENT

| Area | Protocol / Guarantee |

|---|---|

| Projects privatization | Autonomous 3D cubes (“permissioned”) |

| Securing nodes | IDs mixing CSPRNG and algorithmic determinism |

| Securing data | Global chain sharding |

| Securing tokens | Anamorphic cryptography + Merkle Tree (hash) |

| Token uniqueness | KYT for non-fungible tokens (NFT) |

| Securing exchanges | Homomorphic encryption + Vernam “One Time Pad” |

| Language-secured exchanges | SALT/SLU language creation (Synchronous Artificial Languages for Transactions) |

| Securing transactions | POI analysis (Proof of Identity) |

| Securing consensus | Random selection of Approvers (DAG) |

| Language-secured consensus | SALT/SLU language creation |

| User identification / Authentication | MFA + Captcha + Q/A + optional KYC |

Secure. Guarantee. Enforce.

Technologies, Cryptographies, Protocols

1. Languages

Javascript + Nodes

The majority of operations performed on SEGMENT (transactions, storage, verification, interactions) take place directly on each connected machine (UA: User Agent). For this reason, SEGMENT makes extensive use of ES6 as its primary language, along with Node.js for server-side processes (Gossip machines).

Interactions involving IoT devices rely on Go or Python.

User interfaces are written in React.

→ All these programming languages are already familiar to web developers; no additional learning curve is required.

2. Machines

Nodes statuses

Connected machines in SEGMENT are, by definition, full-node UAs, equipped with all the capabilities and tools required to perform any type of operation — whether they are powerful computers, simple smartphones, or IoT devices.

Each node is individually identified by a complex numerical sequence offering thousands of billions of billions of distinct possibilities, effectively preventing identity theft (Sybil attack) through brute-force attempts. See the “Security” section below.

SEGMENT enables the creation of GOAs (Groups of Associated Objects), which share a common identifier and a common wallet, thereby making it possible to create temporary DAOs — opportunistic organisations formed to accomplish specific tasks.

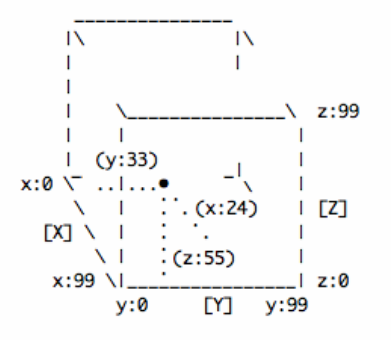

Technically, an x,y,z point of each cube (see section 3 below) is dedicated to hosting DAOs; no individual machine can be located there. Each machine holds a certain number of shares in the DAO (transferred from its own wallet into the DAO’s wallet), and a smart contract distributes revenues among the DAO’s participants according to predefined rules. The DAO is dissolved once its mission is completed.

3. 3D Cubes

Distinct application projects

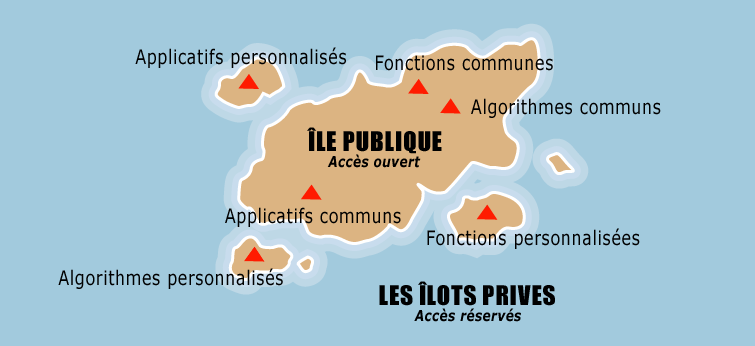

SEGMENT is architecturally composed of several thousand virtual 3D cubes, each completely isolated from the others. Every cube represents a distinct project or client and is inaccessible to machines that are not explicitly invited to it (private blockchains). One particular cube is public and open to all machines: this is SEGMENT as a public blockchain. The full architecture of these coordinated cubes makes SEGMENT a hybrid blockchain.

Each 3D cube consists of one million distinct points (x ranging from 0 to 100, y from 0 to 100, z from 0 to 100), and each x,y,z point can host one million different machines, individually identified from 000000 to 999999. This spatial cube+point organisation enables up to one trillion machines to exist within a single cube — more than 120 machines per human being on Earth… and SEGMENT contains thousands of such cubes.

Because each cube/project is autonomous, it can develop its own application layers, features and specific protocols, built through the distributed API that sits on top of the base applications, functionalities and protocols that make up SEGMENT’s Core.

Any owner of a cube/island (company, institution or association) can therefore decide — depending on the type of project and the required level of confidentiality — whether access should be public or strictly restricted to its own network.

4. Data

Chains of blocks

Every machine owns a part (Sharding) of the global blockchain, which it does not exist anywhere in full version. The information is held encrypted: the cryptographic protocol will be different according to the machines, their characteristics, their IDs, their positions in the 3D cube, which makes their decryption complex to carry out without knowing these characteristics and specific criteria. It is not possible to reverse engineer the initial encryption.

This division of the global chain into segments forces the Nodes to dialogue constantly to access the data they need to perform any operation.

Segmented chains are made up of stacked blocks. These blocks are of different types: some describe wallets (owner + timestamp + type of content + value contained + control hash*), others contain portions of smart-contracts, others specific dynamic data describing the status of the machine at a given moment of an ongoing process concerning it: transaction, approval, etc.

* The control hash (Merkle Tree) is used to verify the signature of the 5 Approvers who validated the transaction..

5. Objects

Tokens

SEGMENT is a global token management tool. A token is a good (physical or digital) that can be individually identified and whose representation can be digitally stored.

The objects contained in the block-wallets can be of different types and of different natures. Each 3D cube/project built on SEGMENT can define the type and nature of the tokens created, held and exchanged: fiat or crypto currencies, real objects (for example: type, serial number, vehicle registration number), digital objects (steganographed reference in a photo signed by its author), CA holder tokens (see the dedicated DAX page: “Digital Assets Exchange” https://segment.pm/), capacities and rights (access , votes, asset disposals …), but also geolocated positions, reference to an object on IPFS, etc.

SEGMENT differentiates between fungible tokens and non-fungible tokens (NFT). If I borrow 10 (CHF, euros, dollars) from you and give you a 10 dollar note the next day, we are okay even if it is not the same note as the day before because fiat currencies are “fungible “: one is exactly the same as the other. They are indiscriminately interchangeable. On the other hand, if I ask you to lend me your Ferrari and the next day I will give you a Dacia to you, we are facing a serious problem: cars are non-fungible objects. One does not merge with the other.If tokens are defined as NFT, they inherit specific identifiers allowing their production and movements to be traced from one account to another: KYT (“Know Your Token”) is the equivalent in SEGMENT of KYC (“Know Your Customer “) banking: an individual identification. A token will or will not be NFT, and its trading conditions will then be different. This “object ≠ object” differentiation is important in many cases (DeFi for example).

What is the essence of “token”?

This is one of the direct consequences of the application of the blockchain to multiple sectors outside of finance. With each new use case being tested on the surface of the earth, a token is produced which is a unit of account, a quantum of information in fact, which is certified and authenticated with the blockchain. It is this action of manufacturing a particular unit of work that is called tokenization. From something continuous or mass, we have extracted units that can be commercialized, exchanged, valorized, stored if possible, transported, shared…

For example for the time given to others at a local level: authenticated, certified and in a way valued in the eyes of all through the transparency provided by the blockchain. The volunteer hour (crypto-time? or crypto-benefit? : ) becomes a token that can itself be exchanged for an energy token. With an advantage: transparency, visibility, training and emulation effect … and multiplied action at long distance as we will see later.

Pierre Paperon : “The tokenization of the world”.

6. Cryptography

Anamorphic cryptography

Anamorphic distortion: only the user placed in the right place is able to restore the original image.

Imagine a magical device allowing you to speak out loud in the middle of a compact crowd and to be understood only by the people to whom you are sending your message: this is the best definition that can be made of anamorphic cryptography, a SEGMENT creation intended to anticipate future quantum attacks.

Each machine (or group of machines) being positioned in x, y, z in its virtual 3D cube, the emitter and the receiver(s) are separated by a certain angular value in the three directions x, y and z: DAE = distance, azimuth and elevation. A simple trigonometric calculation makes it possible to measure this distance and the orientation of the line connecting the transmitter and receiver(s). Starting from the point x, y, z of the transmitter, there is therefore only one point validating predefined values of angle and distance.

Anamorphic cryptography simply consists of writing a message posted publicly in the Gossip (dial public machines) encrypted in such a way that only the machine (or machines) of the destination point x, y, z can understand it… and therefore use it. When Alice wishes to pass a message to Bob, she will therefore produce an encrypted message according to these values strictly specific to Bob + Alice.

A little explanation. When registering an Alice’s machine, a point of the 3D cube is algorithmically assigned to it, for example x:21 y:52 z:44; this value 215244 is written in its stored identifier encrypted in its data. As seen above, Alice also inherits a 6-digit randomized number, for example 034982. Same for the Bob’s machine which is worth for example 458902 in position x, y, z and 800241 in randomized number.

A third machine, from Chris, is by chance on the same x, y, z as Bob’s but its number is 378125… If Alice encrypts her message using the permutation 215244 → 458902 + 000000, Bob and Chris will understand her message since both are on the same point of the cube. But if Alice encrypts it using another permutation: 215244 → 458902 + 800241 then only Bob will be able to decrypt it.

About these “permutations” which allow anamorphic cryptography to secure Node-to-Node dials: each x, y, z value (position of the machine in its 3D cube) presents a million variants, ranging from 000000 to 999999. Starting from 62 keyboard signs AZ, az- and 0-9 (to simplify… SEGMENT includes many more) there are 62! Possible permutations, that is to say approximately 3.146997326e85 (= 85 zeros behind, so a bunch of billions of billions of billions).

Each of these permutations can be numbered and produced individually. We can thus find the exact permutation of Bob, which would be the 458902nd if we only took into account its x, y, z position. For example, that would give the table e4B8cmGPu2 ... Zk1bS (our 62 permuted signs). In reality, in SEGMENT it is much more complicated since there are several hundred usable signs and the permutations for each machine take into account not only its position and number, but also the name of its owner encoded in 6 digits also, the characteristics of the machine (Fingerprint on the OS, its processor capacities, etc.) or even the timestamp of its registration.

Dynamic Transposition

Enciphering individual characters (Stream Cipher) allows ciphering to begin immediately, avoiding the need to accumulate a full block of data before ciphering, as is necessary in a conventional block cipher.

One goal of Dynamic Transposition is to leverage the concept of Shannon Perfect Secrecy. This occurs when the ciphering operation can produce any possible transformation between plaintext and ciphertext. As a result, even brute force no longer works, because running through all possible keys just produces all possible block values.

One interesting aspect of Dynamic Transposition is a fundamental hiding of each particular ciphering operation. Clearly, each sign is ciphered by a particular permutation. If the opponent knew which permutation occurred, that would be useful information. But the opponent only has the ciphertext to expose the ciphering permutation, and a vast plethora of different permutations each take the exact same plaintext to the exact same ciphertext. As a consequence, even known-plaintext attack does not expose the ciphering permutation. The result is an unusual block cipher with an unusual fundamental basis in strength.

Terry Ritter: “Ritter’s Crypto Bookshop”Let’s come back to permutations: each machine therefore has its own table which belongs only to it.

If on 10 qwertyuiop signs (to simplify to the extreme) Bob’s permuted table is rypwoeituq and Alice’s is oeypqtuewir, Alice wanting to send the qwerty code to Bob will send him the public message ouyqep (her “q” is “o”, her “w” is equal to “u”, etc.) which he will understand as meaning qwerty. Chris who owns the urqpituyew table will see Alice’s message getting across since it is public, but he will understand utqirp… which means nothing.

In actual use of SEGMENT, if the qwerty message means “do this” as a contractual condition, only the Bob’s machine will understand it and perform the requested operation. Anamorphic cryptography is obviously much more complex than that but we will address this question in another chapter: that of transaction languages.

Homomorphic encryption

Almost all blockchains (except SEGMENT, of course…) use cryptographic systems with double keys, private and public. It is the direct application of the famous Kerschoffs Law which says that “the security of an information system can only reside in the existence of a key kept secret”. These key systems are currently based on a complex factorization of prime numbers based on mathematical functions of elliptical curves (ECDSA) allowing to produce a public key from a private key.

This double key system has many advantages but also some disadvantages:

• Losing your private key is losing everything, and having it stolen is everything being stolen. Hence the absolute obligation to protect it, some do not hesitate to place it in a bank safe.

• There is no guarantee that the hash produced does not undergo possible collisions, i.e. where 2 different values produce an identical hash. This collision was experienced and documented two years ago on SHA-1 hash protocols in a research lab where connected computers produced this collision in a few weeks of brute force attack. Blockchains use SHA-256 protocols that are impossible to collide at present, but the probable fairly rapid arrival (10 to 20 years) of quantum computers poses serious threats to SHA.

• But there is worse: it is today considered as absolutely certain by all the experts that the ECDSA curves will not resist quantum attacks since the factorization of extremely high prime numbers (1024 bits) will be operable in a few minutes, and therefore that starting from any public key we can easily find the private key from which it was generated. Which, roughly, amounts to saying that all our little secrets will be displayed in the public square.

This is why, since the beginning of its conception, SEGMENT has turned away from these cryptographic protocols to invent its own, in particular anamorphic cryptography. But this alone is not enough: it certainly forms the cryptographic backbone of exchanges, but if the methodical value-by-value exploration of its permutation tables is today technically impossible (billions of billions of billions of possibilities… exactly 821657867364790503552363213932185062295135977687173263294742533244359449963403342920304284011984623904177212138919638830257642790242637105061926624952829931113462857270763317237396988943922445621451664240254033291864131227428294853277524242407573903240321257405579568660226031904170324062351700858796178922222789623703897374720000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000 …), it may not be in 15 or 20 years.

This is why the homomorphic is added to the anamorphic.

Homomorphic encryption simply consists (everything is relative) in entrusting a Node or several of them with the algorithmic calculation of a result from encrypted data and in returning this result without having to decrypt this data. In other words, the output result will be strictly the same as that produced by performing the same calculation with the initial unencrypted data. These are interesting algorithmic functions because they come under what in cryptography are called “ZKP protocols”: “Zero-Knowledge Proof”.

Suppose you have some top secret information that only you and I know… We are in public and I have to make sure you are the person I am looking for: if I ask you to whisper the secret to me in a low voice, someone with a very powerful microphone will be able to hear it, someone who can read lips too. If I ask you to write it to me on a piece of paper someone with a telescope from a neighboring roof can read it, someone can tear it out of my hands. In short, the secret is no longer a secret.Incidentally, in cryptography these are called “auxiliary channel attacks”: security researchers have demonstrated that an RSA private key entered at the keyboard could be found by “listening” to the work and the timing of the operations of a microprocessor. We were even able to reconstruct a conversation held between two people in a closed room by observing the tiny vibrations of the glass of a simple bulb on the ceiling… In other words, attacks by auxiliary channels are things to be taken very seriously.And so to be sure that you are the right person, I am going to ask you not to tell me the secret, but to prove to me that you have it without ever having disclosed it: ZKP = “Zero-Knowledge Proof”. For example, if we are talking about a specific person, I will ask you for his date of birth. Even if a hacker listens to us, the chances of finding who we are talking about among the 300,000 people born on the same day in the world may take a while. Except that for SEGMENT it is not 300,000 possible variants that come into play, but billions of billions of billions.

Homomorphic ZKPs are used in SEGMENT to evaluate POIs (Proofs of Identity) ensuring that each machine* is indeed who it claims to be. Any fraudulent machine (Sybil or other attack) is immediately detected by others (POI failure) and its data reset to zero: a hacker with a wallet with all his cryptocurrency fortune inside will lose everything, with the impossibility of reconstituting his deleted data. He will of course be able to save this data and reconstruct them artificially on his attack machine, but his concern will be that no machine on the network will recognize him since any reference to his machine will have been deleted on all machines containing it in their Shards. He will only have to attempt an 80% attack (see below) but that’s another story.

*Cryptography based on machines

Rather than being restricted to arithmetic operations, mechanistic cryptography tends to use a wide variety of technical components which may not have concise mathematical descriptions. Rather than simply implementing a system of math expressions, complexity is constructed from the various efficient components available to digital computation.

Terry Ritter : “Ritter’s Crypto Bookshop”In its exchanges-machines SEGMENT uses a variation of the NewHope algorithm (Homomorph Lattice-based Cryptography Quantum-Resistant Ring-LWE).

One Time Pad cryptography (disposable mask)

It has been known and demonstrated for nearly a century that the ideal cryptographic security exists: it is the “disposable mask”, or Vernam protocol.

We take a message, we permute each sign according to a disposable grid (it should NEVER be used again) and we send it. Its recipient, holder of this grid, will therefore be the only one able to decrypt and understand it.

The “red telephone” which connects the leaders of this world uses a Vernam in “audio” version to secure their exchanges.The only problem for almost a century – and it has been insoluble for a long time – is that we did not know how to transmit this unique grid to the recipient of the message while being certain that no one could grab it in the process…

• if I send him in the message it is no longer a secret grid,

• if I send it before, there is no guarantee that it will not have been intercepted,

• if I send him by email or SMS nothing says that his email or his phone are not listened to,

• if I pass it according to a code agreed between us, nothing assures me that a MIM (“Man-in-the-Middle”) attack has not become aware of it, etc.

And if I reuse the same grid even twice, nothing tells me that the first message was not stored by an attacker waiting for the continuation, and that comparing the first and the second message it will not succeed find occurrences, similarities, redundant frequencies and by brute force attack reconstitute both… This is exactly what happened in 1943 with Enigma, the coding machine of the German army, cracked by Alan Turing, mathematical genius and cryptographer who, for the occasion, invented the first computer in the world.

‘Perfect Secrecy’ is defined by requiring of a system that after a cryptogram is intercepted by the enemy the a posteriori probabilities of this cryptogram representing various messages be identically the same as the a priori probabilities of the same messages before the interception… perfect secrecy is possible but requires, if the number of messages is finite, the same number of possible keys.

Claude Shannon : “The Perfect Secrecy”Thanks to the work of talented cryptographers, a solution has emerged in recent years: “Secret Sharing”. In SEGMENT we mainly use an adapted version of the Blakley algorithm (SSB) and more rarely that of Shamir (SSS).

CSPRNG

Behind the acronym CSPRNG “Crypto-Secured Pseudo-Random Number Generator” hides an algorithmic set in charge of producing random numbers without the possibility of scaffolding simulation algorithms capable of producing non-equiprobable output frequencies.

Classical computer functions for producing random numbers of the Math.random() type generate predictable occurrences over the long term in their order of appearance.

A sequence of numbers is considered “absolutely randomized” if this sequence is:

• equiprobable: for each digit there is the same chance to obtain any sign of the sequence,

• uniformly distributed: the probability is the same over time for each draw,

• statistically independent: there is no causal link between a given group of numbers and any other randomly selected group,

• unpredictable: it is impossible for a given input to predict its output,

• not reproducible: it is impossible to obtain voluntarily the same result whatever the number of trials.

The CSPRNG SEGMENT are built on unpredictable Shannon entropies with equiprobable outputs.

A sequence of bits might be called “ideally random” if each new bit could not be consistently predicted with other than 50 percent success, by any possible technique, knowing all previous bits.

Randomness is an attribute of the process which generates or selects “random” numbers rather than the numbers themselves. But the numbers do carry the ghost of their creation: If values really are randomly generated with the same probability, we expect to find almost the same number of occurrences of each value or each sequence of the same length. Over many values and many sequences we expect to see results form in distributions which accord with our understanding of random processes. Randomness can produce any relationship between values, including apparent correlations (or their lack), which do not in fact represent the systematic production of the generator.

An “ideal” random number generator repeatedly selects among the possible values. Ideally, each value has the same probability of being selected, and each selection is made independent of all other selections (Random Sampling). In this way, any possible sequence can be created. Although some apparent patterns will occur by chance, an ideal CSPRNG produces no predictable patterns.

Terry Ritter: “Ritter’s Crypto Bookshop”

In addition

SEGMENT also uses several other cryptographic protocols to secure its exchanges and data, for example:

• the ISO 13616 mod97 protocol (that of bank IBANs, credit cards, social security numbers, etc.),

• the conversion of complex data BYTES [0,1]→TRYTES [-1,0,1] either to reduce their weight, or to hide their value, or to check that the result of a calculation is in conformity,

• decimals of π: a value is replaced by its first occurrence in the decimal places of PI, for example the value “999” is in 1752nd position … the code 1752 once anamorphosed into ü_4ç for Bob will therefore actually be worth 999 for him,

• a hash by key protocol (Siphash), considered more secure than SHA, MD5, TEA or AES: a hash is produced starting from a homomorphically or anamorphically shared encryption key,

• Salt & Pepper: a data is endowed with an indeterminable number of unnecessary additional signs preventing it from being found by comparing its length with supposedly similar data. Salter consists of adding specific signs to a specific data, and pepperizing consists of determining a number of random signs to be added to all the data whatever they are (global scope),

• Message Authentication Code (MAC): machine-to-machine messages are signed with a code guaranteeing that they have not been altered or modified by an interceptor (MIM attack: Man-in-the-Middle),

• etc.

7. Protocols

Transactions and their languages

For SEGMENT, any request is a transaction, whether it involves an exchange of values (Alice pays Bob 100 account units), a machine ID identification/authentication or the geolocated position communication of a delivery drone, arrived at destination.

When a transaction is launched by a machine on the Gossip (public dial) it is always in anamorphically encrypted form: only its recipients can understand what to do with it. What the message contains will also be encrypted (see the methods above) prior to its anamorphization. There is therefore a non-negligible risk of collision: for example the message B_4û(Cn22kT posted by Alice to Bob could mean “Do this” for him, but also by bad luck “Here is my secret identification code” for a Chris’s machine listening to the public Gossip, which can be a problem.

To overcome this, SEGMENT uses among other techniques a system of marking (“flag”) of the messages: if for example the message once anamorphically decrypted by its recipient begins with “/@” and ends with “*/” then it is really intended. Any other interpretation (for example “Ub” and “4_” as surrounding flags) does not make sense for any other machine.

A complete transaction is carried out in several stages:

1. Alice says “I am Alice” by pseudo-randomly anamorphosing it according to strict algorithmic rules: a point x, y, z of its 3D cube must be designated as PTR (transaction point).

2. if at least five machines (configurable number according to the cubes/projects: the more machines to be found, the more security of the transaction will be ensured but the longer it will be…) are present at this point we go to step 3. Otherwise, if only 1 to 4 machines are found, they deport the PTR by acyclic DAG at the points x ± iy ± 1 z ± 1. There cannot be 0 machine on the PTR: when they register, the machines are algorithmically (and not randomly) endowed with an x, y, x position. The PTR is guaranteed by this protocol.

3. Once the 5 transaction approving machines are selected (if there are 10 or 100 or 1000 on the PTR the protocol chooses 5 randomly), they randomly determine (by CSPRNG) an LTR, a transaction language. This is a particular version of anamorphism where certain permutation tables on a certain number of signs are constructed in such a way that neither these tables, nor some of these signs are shared by other machines not concerned by the current transaction.

Like all languages in the world, this LTR language has a syntax, a vocabulary and a grammar. As there are millions of millions of possible LTRs and its lifetime will be that of the complete transaction (3 to 5 seconds), no attack is to be feared on this LTR while it is in use.

This LTR uses certain signs as verbs (grammar), others as syntax, others as concepts (vocabulary). For example, the sentence ÄÖÌ[ÈW`ûôèì+&W?+ò/ passed in the public Gossip by the 5 approvers will mean S[W?U=Alice&$=1&h), which, structurally, will ask for Send{Wallet[user=Alice]+[token=euros]+timestamp} to other machines on the network (see point 5 below: “parent machines”).4. Once the LTR is created the approvers will ask Alice to confirm her ID (POI). Once this has been acquired and validated, they will ask her what she wants to do: “pay Bob 100 units”.

5. Then, the approvers ask certain machines in the network (selective sorting by “family” affinities between machines: its brothers, its cousins… it is written in the ID/DNA of each machine) to return the previous request to them : “what is the current value of Alice’s wallet in euros ?”.

6. Alice’s “parents” return this value that they find decrypted in their shards and return it encrypted in LTR to the approvers. If all the returns (say 20 or 30) say the same thing (“Alice had 1500 euros on such day at such hour/minute/second”) the consensus is immediate: the transaction is accepted: Alice is indeed Alice and she holds in euros enough to pay Bob 100… Then, the approvers ask Alice’s “parents” on the network to update her wallet (new timestamp + value = 1400) and Bob’s “parents” to do the same: new timestamp and value + 100.

7. If the answers are discordant, we enter a cycle called in blockchain cryptography “the Dilemma of the Byzantine Generals” (see below, 9. BFT): faced with contradictory orders, how to make the right decision? In this case, each approver takes note of the 20 or 30 responses and assigns each response a reliability %; by adding up the 5 percentages (hers and the other 4) and comparing each % produced by others to hers, each approver determines whether it agrees or not. If at least 4 out of the 5 machines agree, each with more than 90% reliability, the consensus is achieved and the transaction accepted (see point 6 above for the rest: block updates).

8. If more than 80% of the “parent” responses are identical (same timestamp and same value) and 20% differ (older timestamp and other value), we consider that these 20% are non-updated parents: we do not take this into account. They will be updated as soon as the transaction is completed.

If among all the answers one offers a very recent timestamp and an abnormally high value (all say that Alice at 1500 euros but only 1 credits her with 15 million euros…) we consider that this machine is fraudulent and it is instantly reset.

These transaction protocols as set out here are relatively simplified to facilitate approach and general understanding. In the reality of SEGMENT, they are much more complex and would require complete technical documentation.

8. Security

Datas and Transactions

As no data is stored on any server, their security is not “physical” in the sense that it would be necessary to be concerned at the same time with the regular backup of the databases on backup servers, with their protection against malicious attacks and against the hardware infrastructure itself. On the other hand, it is up to each device holder (Node User-Agent) to ensure their security against loss or theft, as he would with his credit card or private key. We will come back to this in the next chapter.

By design, no one – no access provider, no device or component manufacturer, no application developer – can access the basic data that allowed the creation of the machine ID (position, number, fingerprint , timestamp, etc.); therefore trying to reconstitute them becomes a difficult task: for each of these values there are 3644153415887633116359073848179365185734400 variants; finding the right one by brute force would take 2.7577419697518847e21 centuries (with 21 zeros behind) at the rate of one test/second.

With this exception, all the algorithms of SEGMENT are of type ADP:

• Auditable: they can be consulted and auscultated.

• Deterministic: for an equal input they will produce an equal output, always the same.

• Predictive: at a given entry, they produce an anticipated exit without necessarily needing to be executed.

There are many possible attacks on current transactions and all call for specific responses:

• the accidental discovery of the LTR table can be immediately excluded within 3 to 4 seconds of a transaction; once this is over, dynamic LTR is no longer useful.

• a machine can attempt to pass itself off as another (Sybil attack). The attacker just needs to access the data on another machine that he manages to take control of to replace his data with that of the hacked machine. The IDs are designed in this way – notably through the fingerprint – that reconstituting all the data necessary to extract exactly the same series of figures in the end is an almost impossible mission since whatever it does, the two machines will never be exactly the same… One micro-variant will produce different results, and different results = automatic machine reset.

• another option mentioned above: the attacker stores his current data separately, tries new ones then finally reinstalls his own after various failures to be recognized (consensus on failed POI). Problem: no machine will recognize its own after it has been reset.

• last option: the massive attack to take control of the system by creating as many machines as necessary, real or virtual. New problem for our hacker: not knowing how many machines are connected to each point of the cube, he will have to create more than 80% of them to be almost sure to have an overwhelming majority on each point, in order to be sure that at least 4 of his will be randomly called to become approvers of transactions he wishes to divert in his favor. A million points times 100 machines on each point = 100 million machines to be created.

• following problem: it is statistically speaking unlikely that all are randomly equitably distributed in the 3D cube: it can thus end up with 1000 machines on a point and strictly none on the adjacent points; the chances of owning 4 out of 5 machines (80% as the certainty threshold of being called upon to transact) would require at least doubling the number of attack machines: from 100 million we go to 2 or 300 million. Not easy to achieve, neither in time, energy nor money. While classic blockchains guarantee that holding 51% is enough to invalidate a legal transaction block to force validation of an illegal forked block, in SEGMENT this type of attack is not possible.

• attacks by double spending (an attacker launches two simultaneous transactions for a total amount exceeding his assets) are not possible either in SEGMENT: when Alice launches a transaction, her status drops instantly from 1 to 0. It will return to 1 (capacity to start a new transaction) a few seconds later, when the cycle of her first transaction is completed.

• an attacker saves the current dials on his own machine and, by force, manages to locate enough constants to determine who is talking to whom and what is being said. SEGMENT producing several million LTRs (SALT/SLU type transaction language: Synchronous Artificial Languages for Transactions on Semantic Lexical Units), it is impossible to identify redundant frequencies of occurrences on very short sequences: an average message only includes about twenty signs.

• if he leads a brute force attack to test all possible languages by permutations of signs, the result obtained is itself an encryption (no human language exchanged since SEGMENT is only a “micro-company of machines”) there is undecidability on the “real” result: starting from B4)n8i and obtaining thousands of results [ 5Fv-hL, P4dcàI, …, 67gyPz ] does not say which is the real usable.

• if he tries to manually and intentionally post series of fake encrypted messages to evaluate the results in return (and thus manage to take control of the Gossip), at worst nothing happens (no machine understands), at better, the “real” return remains undecidable.

• if he tries to find his kinship to force all his “brothers/cousins” to over-evaluate the content of his wallets for falsified transactions, not only the updating of their blocks can only be carried out on instruction of 5 Approving machines with the same x, y, z position but in addition the control hash of each wallet will no longer be consistent with its contents.

… these are just a few examples, we have identified more than 30 different types of SPOF (Single Point Of Failure) attacks possible on SEGMENT and all of them have their answer.

9. Resilience

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT)

Byzantine Fault Tolerance is the property of a system capable of resisting the class of faults derived from the Byzantine Generals problem. This means that a BFT system can continue to function even if some of the nodes fail or act maliciously.

The “Byzantine Generals problem” assumes that each general has its own army and that each group is situated in different locations around the city they intend to attack. The generals need to agree on either attacking or retreating. It does not matter whether they attack or retreat, as long as all generals reach consensus, i.e., agree on a common decision in order to execute it in coordination.

Each general has to decide: attack or retreat (yes or no). After the decision is made, it cannot be changed and all generals have to agree on the same decision and execute it in a synchronized manner. Each general is only able to communicate with another through messages, which are forwarded by a courier: the central challenge of the Byzantine Generals’ Problem is that the messages can get somehow delayed, destroyed or lost. In addition, even if a message is successfully delivered, one or more generals may choose (for whatever reason) to act maliciously and send a fraudulent message to confuse the other generals, leading to a total failure.If we apply the dilemma to the context of blockchains, each general represents a network node, and the nodes need to reach consensus on the current state of the system. Putting in another way, the majority of participants within a distributed network have to agree and execute the same action in order to avoid complete failure.

Through its pre-block consensus protocol with >=80% approval SEGMENT is 100% BFT: one or more nodes can lie and cheat without altering the final result.

10. Users

Controls and KYC

In a classic system for managing interactions between user and service, we use the scheme [User+UA]→Service: User uses his UA (his machine) to connect to the service, whether by entering a login couple + password, or by entering a secret code, or by entering anything else to authenticate User.

In SEGMENT, the User/Service interaction is designed differently: it applies the User→[UA+Service] scheme. The UAs are connected to SEGMENT as actors (Nodes) – they are the ones who dialogue, transact, interact, make decisions – without User having to intervene. It remains to connect it to his machine and authenticate it.

Therefore, the question is: when a “UA as Node” machine initiates a transaction on the network (Gossip), how can you be sure of User?… In other words: how to create trust without an outside third party guaranteeing the veracity/reliability of information? This is the raison d’être of blockchain technologies.

Concretely, how can you be sure that when a phone initiates an “Alice pays 100 to Bob”, Alice’s phone is in Alice’s hands and not Bob’s… or anyone else’s.

A certain number of control/security devices are implemented in SEGMENT:

• When User registers (or rather registers his machine) he must ask himself 3 questions and give the 3 answers. He will make sure to ask questions that only he can answer… a standard question like “where was I born?” or “what was my first cat’s name?” can allow an attacker (especially a loved one… it happens) to find the answer in a few minutes. On the other hand, the precise and correct answer to the question “where did I eat my first Big Mac?” is more difficult to find the first time. When User initiates a transaction, he is presented with a list of 20 questions including at least one of his own, the others are drawn at random; he must find his question(s) and answer them without possible error. A Levenshtein/Jaro-Winkler script analyzes its answer and determines whether typing errors (lower case instead of upper case for example) are disabling or not.

• The data to be entered by User on the keyboard is carried out on a virtual keyboard of random size/position on the screen: attacks by Keysnuffing (capture the signs entered on the physical keyboard) or by detection of the place where the screen was clicked become impossible.

• A CAPTCHA based on the machine’s own permutation table presents a series of 8 successive characters to reproduce, ensuring that User is not an automated bot to attack in brute force. These keyboard signs are generated graphically (intercepting their production and their display as ASCII signs is therefore impossible) and the conformity of their input to the virtual keyboard is not built on an equivalence of signs (A == A) but on the graphic forms of signs: how many curves, how many lines, how many angles, how many blanks.

• An MFA process is implemented in SEGMENT: the objective is to ensure that USER is physically him by using 2 referenced devices/UA (he declared a “clone”, see next point). On his UA-1 machine he enters a number he chooses, for example “12345”. An algorithm factors it with its real name reduced to digits (the same as in its machine IDs), factors it with “12345”, hashes the result and returns the first 4 + 4 last signs: a435f0cb. On another UA-2 machine (his phone, his tablet, another PC…), he opens a dedicated SEGMENT URL where he must enter his User name and this hash. The algorithm explores all the possible hashes until it finds the initial value “12345” (so when substr(0,4) + substr(-4) == code), refactors it differently and returns a new hash substring that User will have to return to his first UA-1 machine. Its name being in its IDs, a calculation on this input + its User name (that of the ID on UA-1, are you following?) should give exactly the same result.

In this way we are certain that:

1) User is a physical being and not a bot,

2) that he knows his name/nickname, and

3) that he physically owns the two UAs, and therefore that one of the two UAs has not been lost by its owner and found by someone who is looking for how to abuse it.

MFA (Multi-Factors Authentication) technologies are considered secure, unlike 2FA (Double-Factor) where an online service – banks, platforms – sends a code by SMS to your phone – which can be listened to – to be reproduced on the keyboard – which can also be keysnuffed.

• UA cloning: for reasons of data security, each User is recommended to make a “virtual copy” of his UA on another machine (for example clone his phone on his PC). In the event of loss, theft, breakdown, destruction, or simply in the event of a change of computer or phone, being able to recover your data (IDs, wallets, transaction histories, etc.) avoids the risk of them being permanently lost, or else (in the event of theft) being exposed to having their account hacked.

Once the primary UA has been cloned onto the secondary UA, it does not in fact become a “real” clone: it cannot be used as a transaction machine since its data will not conform to its technical characteristics: try to do so would lead straight to being mistaken for a hacker attempting to usurp an identity with immediate and irreversible destruction of the data that we were supposed to protect, which is a shame.

In the event of loss, theft, failure or definitive change of UA, it suffices to send over the network a particular message for a particular transaction to be created, asking the “parents” of the initial UA to update their blocks for the benefit of the new UA which then becomes definitively the official Node of User.

This protocol being by nature dangerous (imagine a hacker claiming to be making you deactivate your device in favor of his…), the authentication processes exposed above are doubled by other controls not exposed here for reasons of global security.

• A banking type KYC protocol (real identity confirmation: DID “Decentralized Identity“) can be implemented on demand on cubes/projects requiring it, according to the needs and legislation in force depending on the country. Unlike classic blockchains where USER is pseudonymized, in SEGMENT, it is fully anonymized: finding the link between wallets and real identities without access to this function (available only in a cube/SEGMENT project in KYC version) is not possible.

→ SEGMENT is fully compliant with the European GDPR directives on the protection and security of personal data.